Belarus Embarks on A Corruption Sweep

Following the unrest in Ukraine, the Belarusian government has reinvigorated its anti-corruption offensive.

On June 17, former deputy prosecutor-general, Alyaksandr Arkhipau, was sentenced to six years in prison for abuse of office and bribe-taking.

The court found his co-defendant

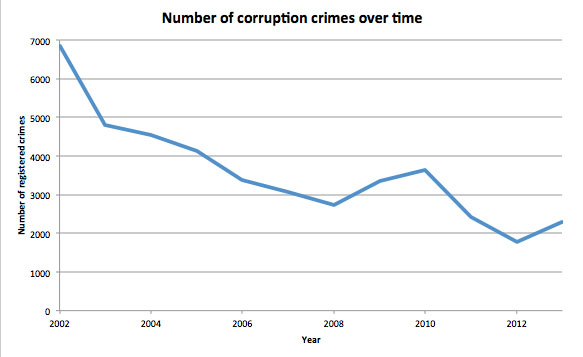

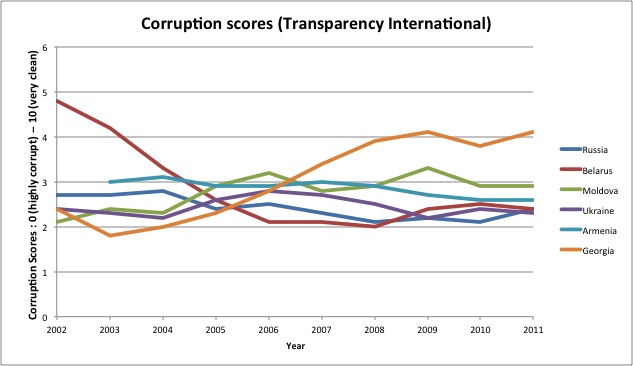

Lukashenka in July 1990: "Take power away from those who don't know how to use it." Following the unrest in Ukraine, the Belarusian government has reinvigorated its anti-corruption offensive. On June 17, former deputy prosecutor-general, Alyaksandr Arkhipau, was sentenced to six years in prison for abuse of office and bribe-taking. The court found his co-defendant Uladzimer Kanapliou, former Chairman of the House of Representatives, guilty of not reporting the crime. Many others, including directors and deputy directors of major enterprises, received corruption charges earlier this year. The corruption crackdown may help Lukashenka’s 2015 presidential campaign at a time when economic growth, a staple of some of his previous campaigns, lags. However, it will hardly eliminate corruption. In the absence of political and economic competition in Belarus, the potential gains to be made against corruption remain limited. Turning Against Former Friends and Allies Kanapliou, one of the defendants in the case, has been close to Lukashenka since the early 1990s. He helped collect signatures for Lukashenka’s presidential candidacy and engineered the presidential hopeful’s first anti-corruption campaign in 1994. When Lukashenka won the presidency, Kanaploiu rode his coattails. He first served as an assistant to the President of Belarus and later as Chairman of the House of Representatives as well as Chairman of the Belarusian Handball Federation. In 2010, pundits speculated that Kanapliou would head Lukashenka’s electoral team in yet another presidential campaign. Indeed, Kanapliou’s name may help Lukashenka’s anti-corruption drive ahead of the 2015 election, albeit in an unanticipated way. This is not the first time the populist leader has turned against his former friends and allies. Even though the president has ruled for the last twenty years, considerable turnover and uncertainty prevail in many other politically important offices in Belarus. Corruption provides one of many possible excuses for rotating and dismissing high officials. In 2013, minister of energy was fired; in 2012, the top echelons Belarusian KGB were purged and the minister of foreign affairs was dismissed; in 2011, the minister of justice was removed; 2010 saw a wave of dismissals in the defence branch following the “teddy-bead affair”; ministers of economics and minister of taxes and duties were dismissed in 2009. If initially analysts optimistically interpreted such high-level purges as signals of change, today they increasingly signal stability and Lukashenka’s power. Corruption sweeps keep Lukashenka’s allies loyal and also show the electorate who is to blame for the nation's endless string of economic problems. When Lukashenka’s friends go astray, their corrupt behaviour is exposed. Some, however, have been brought back into the fold upon surrendering stolen property and apologising. For example, the chairman of "Belneftekhim" Alyaksandr Barouski was charged with abuse of office in 2007, pardoned a year later, and then appointed to be the general director of a major state-controlled company BelavtoMAZ. Summing up Two Decades of Anti-Corruption Battles In 1994 Lukashenka, then a relatively unknown parliamentarian, was elected on a populist anti-corruption platform. He stood out as an outsider, untarnished by any having any direct involvement in the system, whose only prior political engagement was managing a parliamentary committee tasked with investigating governmental corruption. Corruption has remained on the top of Lukashenka’s agenda to this day. There is surprisingly little progress in reducing it, however. According to official statistics, the number of corruption cases has steadily decreased over time, from 6,840 in 2002 to a mere 2,301 in 2013, as shown in the figure above. However, the corruption perception index provided by Transparency International suggests the opposite is true. The index, constructed on the basis of expert and business surveys, shows that Belarus is doing poorly in dealing with corruption, even compared to its neighbours in the post-Soviet space. In 2013, Belarus was ranked 123rd (out of 177 countries) by Berlin-based Transparency International – better than Ukraine (144th) and Russia (127th) but much worse than its EU neighbours Poland (38th), Latvia (49th) and Lithuania (43rd). In 2011, the list of 14 crimes was reduced to 10, with forgery, receipt of illegal remuneration, smuggling, and financing of terrorist activities no longer being classified as corruption-related crimes. Do Anti-Corruption Initiatives Affect Public Opinion? There is no doubt that the top-level officials that have incurred Lukashenka’s ire are indeed corrupt. But will they help Lukashenka’s public image? According to a survey conducted by NISEPI, an independent source of public opinion in Belarus, in June 2013, only 30% of respondents agreed that the president would succeed in his anti-corruption campaign. Another 37.5% believed that Lukashenka himself had dealings with corrupted ministers and was interested in keeping corruption up, while 28% believed he would fail because corruption is deep-rooted in Belarus. In a 2014 survey on the effects of his long-term presidential rule, over a fifth of respondents said that prolonged presidency contributes to the growth of corruption and abuse of office. While twenty years ago Lukashenka was still an outsider, now he is deeply implicated in the system, and his arguments about eliminating corruption may have lost credibility. How Political Competition Undermines Corruption Thus, at least a fifth of the Belarusian public seems to have diagnosed the problem correctly. Among the most important factors linked to corruption is the absence of economic and political competition. Political competition can reduce corruption in a number of ways: on the one hand, the need to get re-elected and the risk of being replaced lowers the appetite for bribes of the politicians in power; on the other hand, frequent turnover among the political leadership diminishes the brazenness with which economic actors can rely on corruption under the protection of any one leader. Additionally, freedom of information and association permits society to monitor public officials, thus limiting opportunities for corruption. The lack of economic competition may also contribute to higher corruption levels, as it allows businesses to seek higher rents, which increases incentives to control public entities to seek bribes. Therefore the prospects for eliminating corruption in Belarus remain dim. The authoritarian nature of the system and the large share of public ownership of enterprises in the economy (about 70% of country’s GDP) make the problem worse. Thus, all of the president's efforts to reduce corruption can have only limited results. Therefore, the rampant corruption in Belarus can be seen as a legacy of its economic and political development in the 20th century. Expert debate about the extent of corruption-induced harm remains unresolved. However, studies suggest that when compared to democracies, non-democratic states are much more likely to suffer substantial economic harm from corruption. The true scale of corruption and its economic consequences in Belarus remain unknown, but it is clear that the new anti-corruption drive will fail to address the root of the problem. IDEA is organising a discussion of Ukrainian events in Minsk. European Cafe hosts public lectures by European intellectuals. Minister of Culture of Belarus, Boris Svietlau handed Fond of Ideas an honorary diploma for organising an exhibition and significant contribution to the development of modern Belarusian art. Legal Transformation Centre (Lawtrend) presents the 5th edition of the quarterly electronic overview of significant events in the field of Internet freedom, protection of personal data and access to information in Belarus. Discussions on Belarus Panel discussion in Minsk. On 25 June IDEA Belarus global magazine invites to the panel discussion devoted to the situation in Belarus in the wake of Ukrainian crisis. Panelists will discuss lessons and consequences of the conflict in Ukraine for Belarus. Among the speakers are Andrej Dyńko, Nasha Niva newspaper, Siarhiej Kizima, PhD, and Aliaksandr Lahviniec, the "Movement for Freedom". The event will take place at the Minsk hotel "Europe". European Café continues hosting public lectures. On 11 June the European Cafe: Open Space in Europe project hosted a public lecture of an Estonian researcher, Dimitri Mironov on transformation of higher education from Soviet to European standards. On 17-18 June political analyst from& Lithuania Gintautas Mažeikis delivered public lectures on the crisis of European humanism in post-Soviet space in Minsk and Viciebsk. A series of public lectures by well-known European scientists is implemented by the Centre for European Studies. Food for Thought Event in Brussels. The Office for a Democratic Belarus and the Wilfried Martens Centre for European Studies invite to the Food for Thought event entitled 'Why Belarus is different'. Dzianis Melyantsou, Belarusian Institute for Strategic Studies and Siarhei Bogdan, Belarus Digest will contribute to the discussion why Belarus is different from the other Eastern European countries; whether the strategic importance of the country changes in view of the Ukraine events. The discussion is to take place on 23 June in Brussels. Really Free Market-2: come and take free! On 15 June the Minsk venue CECH hosted the second Free Fair that is a real alternative to existing market relations based on mutual assistance and cooperation, according to the organisers. Visitors can bring their things and take others' what they need for free. Throughout the day, the Fair will be accompanied by a DJ and closed with a concert. Education Recommendations on the inclusion in non-formal education. First time in Belarus, Association for Life Long Education and the Office of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities have developed a brochure on inclusion for specialists in the field of non-formal education. The brochure's recommendations will allow the providers of educational services to make their activities more inclusive, ie make non-formal education accessible to people with disabilities. Vilnius School on Human Rights. Belarusian human rights school, organised by the international community of human rights organisations, announces a call for participation in the Summer School on Human Rights in 2014. Under the program, participants will learn about the history and philosophy of human rights, as well as methods and means to protect them at the national and international levels. Participation in the program arise open for young Belarusians of 18-25 years old, interested in acquiring knowledge in the field of human rights. Youth:ON leadership course. Youth Educational Centre Fialta invites to participate in the program Youth:ON for leaders of youth organisations and initiatives. The program aims to develop and increase the sustainability of initiatives and organisations working with young people. The program provides thematic training and consultations with local and foreign experts, as well as the Fair of Best Practices. Belarusian NGOs Pact is established in Belarus. A new human rights republican public association Movement for the implementation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights has been established in Belarus. The organisation unites Belarusian citizens on whose complaints the UN Human Rights Committee made or is going to make a decision. A new CSO is to contribute to the execution of Belarus of its international obligations on human rights issues. The organisation has been called "Pact". e-Lawtrend #5. Legal Transformation Centre (Lawtrend) presents the 5th edition of the quarterly electronic overview of significant events in the field of Internet freedom, protection of personal data and access to information in Belarus. The issue covers the period March-May 2014 and raises such topics as future of Internet governance, manual on Human Rights for the Internet user, new restrictions on access to information in Belarus, an overview of Lawtrend activity, etc. "Patriot" launched the first ever Belarusian-language website of the fight club. Patriotgym.by resource created in partnership with the cultural campaign Budzma! The new website has been designed to attract to the club talented children who will support senior colleagues fighting traditions. The website's founders also expect that the example of the Belarusian-language website to inspire other sports organisations to actively use national language. Interaction between state and civil society Citizens help Viciebsk authorities to celebrate the City Day. On 10 June an open presentation of cultural ideas Fair Projects was held in Viciebsk in a new format – it was held in the official venue of city executive committee and with participation of authorities. The Fair initiated by Budzma cultural campaign is designed to improve and expand the official program of the City Day celebrations. The Fair presented seven projects including Dance open air, Fotosushka, Football freestyle, etc. Minister of Culture of Belarus, Boris Svietlau handed Fond of Ideas an honorary diploma for organising an exhibition and significant contribution to the development of modern Belarusian art. It comes about the open-air exhibition Avant-gARTe: From Square to Object and One Hundred Years of the Belarusian Vanguard at Yakub Kolas Square in Minsk. More than ten thousand visitors attended the exhibition; its website was visited by more than fifty thousand users. Officials: Painting Bykau is an ideology issue. Painters were fined for 4.5 million roubles each (about $400) for their attempt to draw Vasil Bykau in the centre of the city. The graffiti on the transformer vault had not been allowed by the city authorities and was removed. The graffiti initiated by the SIGNAL street art community was considered to be dedicated to the writer's 90th anniversary. Baranavichy entrepreneurs ready to protest in Minsk. Private entrepreneurs want to protest against the changes introduced by Alyaksandr Lukashenka's order #222. The order obliges private entrepreneurs to have documents proving where they bought their products after July 1. Belarus Digest prepared this overview on the basis of materials provided by Pact. This digest attempts to give a richer picture of the recent political and civil society events in Belarus. It often goes beyond the hot stories already available in English-language media.

Corruption provides one of many possible excuses for rotating and dismissing high officials. Read more

Why such a drastic discrepancy? Changes in the type of crimes classified as corruption in the Belarusian Criminal Code can explain the drop in corruption crimes observed between 2010-2011.

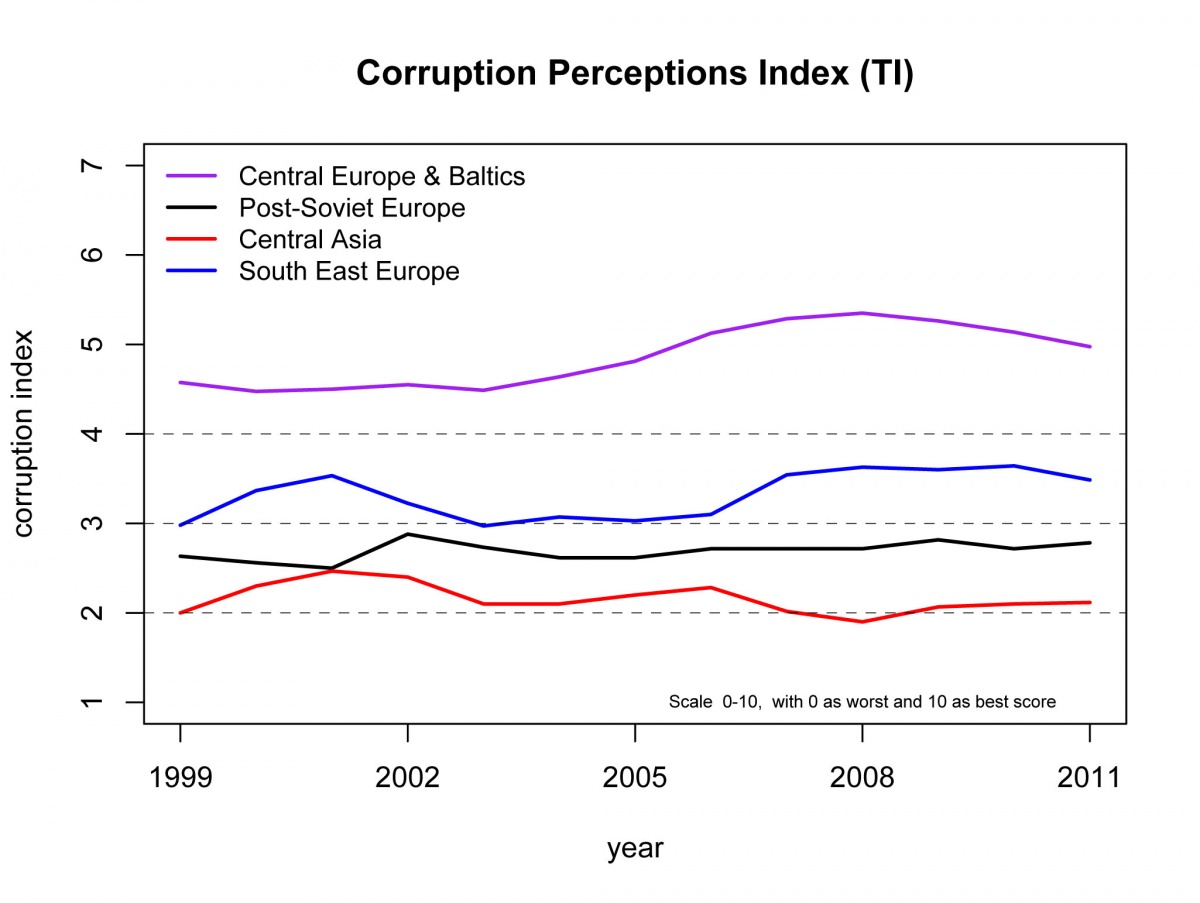

Why such a drastic discrepancy? Changes in the type of crimes classified as corruption in the Belarusian Criminal Code can explain the drop in corruption crimes observed between 2010-2011. Corruption is an ever-present problem in the post-Soviet region. Comparing corruption averages for the post-Soviet and Central European states shows that they are moving in the different developmental trajectories.

Corruption is an ever-present problem in the post-Soviet region. Comparing corruption averages for the post-Soviet and Central European states shows that they are moving in the different developmental trajectories.

Enterpeneurs Ready to Protest, Public Discussions in Minsk – Belarus Civil Society Digest