Belarus, Ukraine, Russia React to Alexievich’s Nobel Prize

Alexievich at a 10 October press conference. Photo by Nasha Niva

When Svetlana Alexievich won the 2015 Nobel Prize in literature, three countries at once tried to claim her success. Headlines across the post-Soviet space called her a “representative of the Russian literature”, a “writer born in Ukraine”, and a “Belarusian writer.”

Yet not only congratulatory remarks, but also hatred, envy, and accusations followed. Reactions were unequivocally positive only in Ukraine. President Petro Poroshenko, the first politician to congratulate Alexievich, wrote: “Wherever we are, whatever language we speak or write – we always remain Ukrainian.”

The award generated mixed opinions in Belarus, with some political activists and literary critics questioning Alexievich’s Belarusian identity because she writes in Russian. In Russia itself some disowned the writer for criticising Putin’s policies and called the decision political. Such divergent reactions to Alexievich’s work reflect deepening divisions in post-Soviet space and betray Belarusians’ insecurities about their national identity.

Inventing a New Literary Genre

Alexievich is the first Belarusian writer to receive the prize, which places her next to such world-renowned writers as Albert Camus, Gabriel García Márquez, Ernest Hemingway, and Boris Pasternak. She will receive the $960,000 prize in an official ceremony on 10 December.

The Swedish Academy credited Alexievich for inventing “a new kind of literary genre” and praised “her polyphonic writings, a monument to suffering and courage in our time.”

Each of Alexievich’s books draws on conversations with 500 to 700 individuals, edited by the writer and presented as first-person monologues. “I chose a genre where human voices speak for themselves,” wrote Alexievich on her web site. “Real people speak in my books about the main events of the age such as the war, the Chernobyl disaster, and the downfall of a great empire.”

Her first two books focus on the memories of World War II. In The War’s Unwomanly Face (1985), Soviet women share their experiences from the front lines. People who survived the war as children tell their stories in The Last Witnesses: the Book of Unchildlike Stories (1985).

In Zinky Boys (1989) readers hear from former soldiers as well as the mothers and widows of those who returned in zinc coffins from the 1979-1989 Soviet war in Afghanistan.

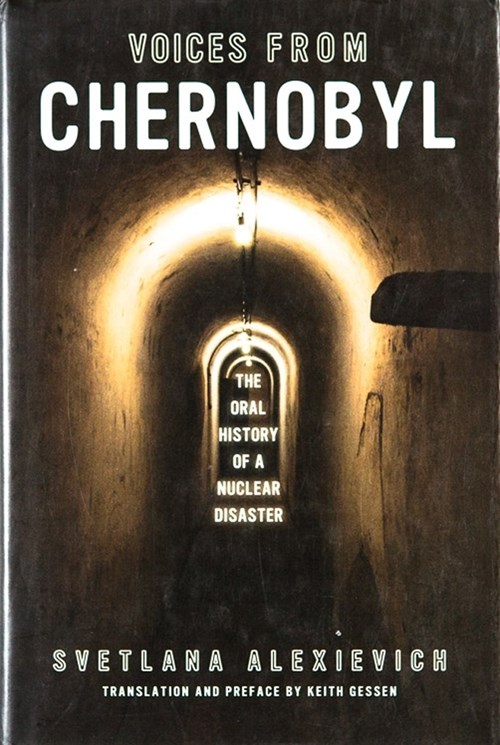

In Voices from Chernobyl (1997), we hear stories of the people scarred by the worst nuclear power plant disaster in the world, which contaminated one fifth of Belarusian territory and killed or sickened nearly half a million Belarusians, Russians, and Ukrainians.

Alexievich’s most recent book, Second-Hand Time (2013), presents individual narratives about the Soviet past, recorded by the writer throughout the 1990s and 2000s.

Alexievich’s Admirers and Detractors

Alexievich has been a favourite to win the Nobel Prize for several years now, generating mixed reactions in Belarus. This time, even President Alyaksanr Lukashenka congratulated the writer, albeit after some delay. He tried claiming credit for Alexievich’s success at a meeting of construction workers in Astravets, Hrodna region, on 10 October: “This means that whatever your political views are, you can … express your opinion in Belarus.”

Yet not all Belarusians celebrate Alexievich’s victory. Some criticise her for writing in Russian and for covering Soviet rather than Belarusian history. Zmitser Dashkevich, a leader of the Young Front opposition movement, reacted on Facebook by asking: “Will Nobel Prize finish off Belarusian culture?” He claimed that “while Nobel laureates bark, the language continues to live!” Belarusian writer Sviatlana Kurs in a Belsat interview said that, as a “fully Belarusian person as far as the language and culture are concerned”, she would have been happier if a Belarusian-language writer had won the prize.

Paradoxically, Alexievich incurred even more criticism from the Russian side, although she did receive congratulations from Vladimir Grigoriev, Russia's deputy minister of the press. Alexievich’s attitudes toward the Russian government and support for the Ukrainian side in the conflict angered some Russian critics.

Dmitry Smirnov, a reporter with the Kremlin Presidential press pool, tweeted that Alexievich won the prize for “hating Russia.” Vladimir Sungonkin, the editor in chief of the Russian tabloid “Komsomolskaya Pravda”, claimed in a 9 October interview with Echo Moskvy that anti-Russian attitudes helped Alexievich win the award.

Why Alexievich Writes in Russian

Alexievich’s biography speaks to the fluid borders and complex identities in post-WWII Eastern Europe. The writer was born in 1948 to a Belarusian father and Ukrainian mother in what is now the city of Ivano-Frankivsk in Ukraine. Alexievich’s family then moved to Belarus, where the writer grew up, studied, and worked.

When asked about her choice to write in Russian at a press conference with Nasha Niva on 9 October, Alexievich explained, “I am writing about a man-utopia, a red person. This utopia lasted for 70 years; another 20 years are spent on getting away from this utopia. And this utopia spoke Russian.” Indeed, heroes of Alexievich’s books are Belarusians, but also Ukrainians, Russians, and Tatars. They all are products of the Soviet system and their shared Soviet past obscures their ethnic identities.

At the same time, Alexievich expressed gratitude to her teachers, Ales Adamovich and Vasil Bykau, both of whom wrote in Belarusian. She also said that while she loved the world of great Russian literature and ballet, “the world of Putin, Stalin” was not her world.

The world of Putin and Stalin is not my world. ~Svetlana Alexievich

In some sense Alexievich’s work is much more representative of Belarus than the work of many Belarusian-language writers. In the 2009 Census, 70% of Belarusians declared Russian "the language spoken at home.” Alexievich’s use of Russian reflects this reality of today's Belarus.

In an interview on 8 October, before the Swedish Academy announced the Prize winner, writer and politician Uladzimir Niakliaeu praised Alexievich for spearheading the breakthrough of Belarusian literature into European literature. He offered a pithy rejoinder to Alexievich’s detractors: “Envy is translated into all languages of the world.”