Modernization Traps for Belarus

The Belarusian government has announced its plans to modernise the national economy. However, the content of the policy package is far from clear. Given the experience accumulated by Belarus and other transition economies, there are reasons to warn about possible traps that modernization policy could set, if implemented unwisely.

The government has announced a new course for modernization to strengthen weakening economic growth. In October 2012, Prime Minister Myasnikovich emphasised that “modernization of the national economy is a priority”.

When reporting to Aleksandr Lukashenka on 14 January 2013, Myasnikovich has been warned that the pace of modernization shall not be slackened. The target of modernization is apparently the state sector of the economy, which still produces about two-thirds of Belarus’ GDP.

Lukashenka summarised his vision of modernization policy at a press-conference on 15 January 2013. According to him, modernization is about “the installation of new equipment to the available production facilities”. Modern equipment is supposed to boost productivity and output growth as the stock of capital is increased – a necessary step to sustain a growth trajectory, which has been declining since from 2011.

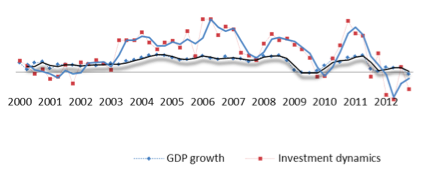

In 2012, real GDP growth amounted to 1.5 per cent, while real investment dropped by 13.8 per cent (see Figure 1 below). Without investment growth, GDP dynamics is in danger of further enfeeblement.

Figure 1: Real GDP growth and real investment dynamics, 2000–2012

Both workers and managers of state-owned enterprises understand that the stakes in the “modernization game” are high. In particular, workers of the wood-processing plants are not allowed to leave their enterprises unless modernization is over.

Independent trade unions – supported in their claims by their Russian and international colleagues – criticised the emergence of “new serfdom” at the Belarusian labour market. Furthermore, a CEO and three managers of Mogilevdrev, a company with modernization underway, are being persecuted for the misuse of public funds granted for it.

Experience of Early Modernizers

In fact, intentions to revive poorly performing economies by the means of technological renovation of industries are not novel for the post-socialist world. In the late 1980s, Poland, Hungary, and Bulgaria and other countries tried to revamp their economies by using foreign money to purchase equipment from abroad. However, export revenues were not sufficient to pay back foreign loans.

First, extensive trading within the socialist block by using convertible roubles had resulted in the lack of hard currency. Second, a more fundamental challenge came from the weak capacity of socialist enterprises to innovate. Foreign equipment was insufficient to substitute a whole system of incentives for managers and workers.

Export-oriented growth of East Asia type failed to materialise. As a result, socialist economies were forced to start their transition to capitalism with considerable levels of foreign indebtedness. This fact allowed international financial institutions as the IMF to exert leverage upon reform, as, for instance, it happened in Poland.

This experience is worth to have in mind when thinking about the design and likely effects of modernization policies in Belarus. In a nutshell, Belarusian authorities see modernization as a task for the state, realised by the means of state investments to state-owned enterprises. Seeing in this light, these policies are not novel, but a continuation of lasting state investment policies.

Predecessors of Modernization

Before the currency crisis of March 2011, investment programmes were a major tool to support technological renovation. These programmes were implemented with the help of cheap loans from state-owned banks. The 2012 World Bank memorandum on Belarus reveals that directed loans are typically three times cheaper than market loans.

At the same time, the gap between factor productivity of state-owned and private companies vary from 20 to 30 per cent on average. Private firms tend to be more efficient than state-owned enterprises.

This fact implies that the efficiency of state investments is lower than private ones. Prior to the currency crisis, directed loans amounted to a half of the total volume of loans, granted typically to agriculture and housing production.

According to a study, conducted by the BEROC researchers in December 2012, the expansion of these loans has not contributed to the improvements in total factor productivity, which reflects the efficiency use of capital and labour in the economy.

Modernization appears to be a call for a more productive use of funds, but there is little evidence in favour of changes in incentives of recipients of state financial aid. Moreover – and this is probably the crucial aspect – private domestic and foreign investors are not considered seriously as major actors of modernization. If foreign borrowing, and not a foreign investment, continues to be one of the sources of foreign cash to purchase equipment from abroad, then macroeconomic stability can be threatened.

The Adverse Effects

Apparently, private investors can be more efficient in implementing modernization plans without state guidance. However, some recent steps of the authorities might keep them away from entering the scene. In particular, nationalisation of two confectioneries and planned amendments to privatisation legislation, stipulating the reservation of special places for state representatives to vote for the absent minority shareholders are the measures that lie far from improving domestic business climate.

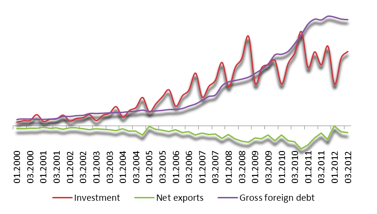

There is a worrisome tendency that increase in real investment is associated with higher foreign indebtedness and lower net exports (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Investment, net exports, and debt, 2000-2012 (3rd quarter)

Source: National Bank, Belstat

Therefore, modernization – even it is understood narrowly as a mere technological upgrade – might bring temporary gains in the form of higher output growth rates, but it contains considerable risks. It is too early to make conclusive statements, but suspicions come from the lower capacity of state-owned enterprises to function as efficiently as enterprises in the private sector.

Without expansion of the private sector and incentives to private investment, the Belarusian economy might continuously require injections of liquidity in the form of state-guaranteed loans. These injections would increase the economy’s volatility without addressing the fundamental efficiency problem. Instead, a vicious circle of more funds–more growth could emerge, with severe inflationary repercussions and high costs of breaking with it.

To summarise, contemporary modernization plans look so far as “old vine in new glasses”. If that is the case, then seemingly new policies would have a limited success. However, if compounded by the measures to support the development of private sector, economic growth can be made more sustainable and less volatile.

Kiryl Haiduk

Senior Research Fellow at the Belarusian Economic Research and Outreach Centre

This article is a part of a new joint project between Belarus Digest and Belarusian Economic Research and Outreach Centre (BEROC) – a Minsk-based economic think tank.