Belarus’ Prisoner Dilemma

Earlier this month, Aliaksandr Lukashenka noted that, during his presidency, the Belarusian prison population has halved. He stressed that despite its dictatorship label, Belarus does not “throw everyone in prison.”

Statistics present a more complicated picture, however. During Lukashenka’s first term, in the mid-1990s, the incarceration rate dramatically increased, placing Belarus third worldwide in prisoners per capita.

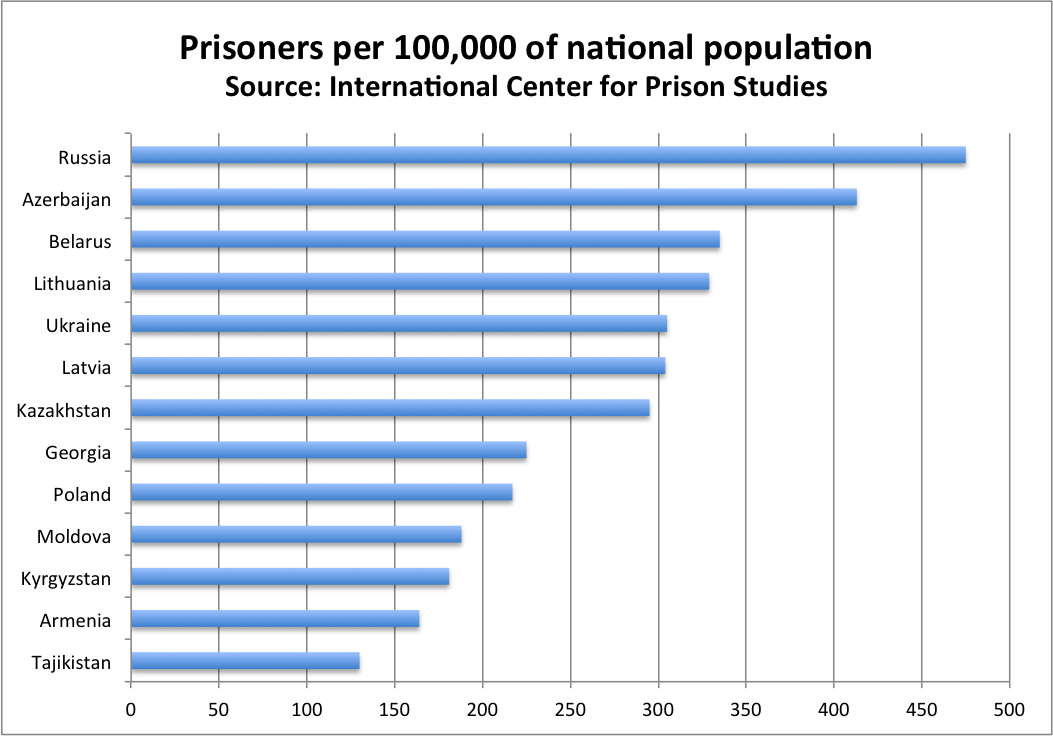

Even though frequent amnesty laws are slowly decreasing its prison population, Belarus to this day has one of the highest shares of prisoners per capita in Europe.

Amnesty laws also provide no lasting solution to the country's high rates of recidivism. Because every second crime in Belarus is committed by a former prisoner, deeper changes to the penitentiary system are needed.

Improving conditions in prisons and reintegrating former prisoners into society are key to reducing the prison population in the coming years.

Why So Many Citizens Serve Prison Sentences

In 2002, Belarus placed third in the world in the number of prisoners per capita, after the United States and Russia. Currently it ranks 25th in the world and second in Europe.

In May 2013, the country had 31,270 prisoners, or about 325 prisoners per 100,000 people; in Western Europe, the median rate is just 98. And this is after having reduced its prison population by more than half since 1998, according to the International Centre for Prison Studies. Clearly, Belarus still has a long way to go.

Why do so many Belarusians go to jail? After all, Belarus's crime rate is not any higher than in other post-Soviet states.

One reason may be the lack of due process. Being charged almost always results in being found guilty. Belarus's likelihood of acquittal (0.3% of all sentences) is even lower than in Russia (3%) and much lower than in Europe as a whole (6%).

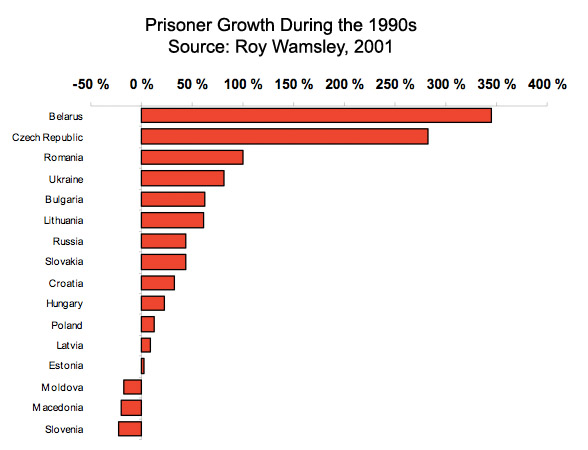

Another reason may be the long-lasting consequences of the surge in incarceration rates during Lukashenka's first term as president. Belarus experienced a nearly 350% increase in the number of prisoners in the 1990s, by far the largest change in the post-Communist space. Many of those imprisoned then have not been released.

To be sure, Lukashenka's zealousness alone does not explain the early incarceration spike. Larger macro-economic forces, unleashed by the dissolution of the USSR, led to profound economic and social uncertainty.

Most post-Communist states responded to rising criminality by increasing pre-trial detention and imprisonment rates and by imposing harsher sentences.

In Belarus, however, the spike in imprisonment was the most dramatic. What is more, its effects have persisted to this day – due not only to the challenges of reducing the prison population, but also to the extremely high rates of recidivism.

Amnesty Laws: Honouring WWII by Emptying Prisons

Belarus's preferred approach to reducing incarceration rates has been passing amnesty laws. Nearly 10,000 prisoners were released or received shorter sentences under the most recent June 2014 amnesty.

This was the 13th amnesty in Belarus’s independent history, dedicated to the 70th anniversary of the Belarus’ liberation from the German occupation. Previous amnesties were timed to the 65th, 60th , and 50th anniversaries of victory in WWII.

Belarusian amnesty laws generally cover prisoners who committed relatively minor crimes, have young children, as well as pregnant, underage, elderly or disabled prisoners. As a rule, amnesties do not extend to political prisoners. However, Ales Bialiacki, the vice-president of the human rights organisation Viasna and one of the best known political prisoners, was released under the 13th amnesty in June.

In Belarus, amnesty is used for political purposes. It signals that the government takes an uncompromising stand against corruption or drugs. This is why Lukashenka frequently repeats that no amnesty will ever cover offenders charged with corruption.

Amnesty also signals the state's willingness to forgive and empathise with its citizens. Indeed, Lukashenka has emphasised that amnesty laws serve the society and are always “free of politics.”

How to Reduce the Number of Belarusian Prisoners

The Belarusian authorities are currently drafting a law that seeks to reduce incarceration rates and change important aspects of the penal system.

The draft law will allow defendants to reduce prison terms by cooperating with the investigation before the onset of trial. The authorities hope that this measure will not only reduce the size of prison population, but also facilitate investigation.

The law also envisions replacing imprisonment with monetary compensation for some types of crimes and decriminalising some behaviours completely.

Even as Belarus sought to reduce the number of future prisoners, it has devoted little effort to improving lives of the current ones. This is important because so far Belarusian prisons have done more harm than good: repeat offenders commit about 50% of all crimes in Belarus.

Recidivists commit every third murder, two thirds of all robberies, more than half of all other forms of theft. Most of them break the law already in the very first year upon leaving prison. Furthermore, in the last seven years, recidivism has increased more than two-fold.

Prisoners Need to be Reintegrated

High recidivism may be partly due to the dysfunctional prison culture in Belarus. Wardens beat and humiliate prisoners.

Last year, political prisoner Mikalaj Aŭtuchovič cut his abdomen in protest to the abuse by the prison administration.

Living conditions in prisons are deplorable. Single cells do not exist, and prison overcrowding is a problem. This produces a lot of diseases.

An even larger problem, however, is the failure to integrate the released offenders back into society. Unlike west European nations, Belarus has not developed an adequate system of post-penitentiary integration.

Last year, the first reintegration project was launched with the help of a 300,000 Euro grant from the EU, as well as the technical guidance by the international Federation of the Read Cross and Red Crescent.

The project seeks to provide psychological, legal, professional, medical, and humanitarian help to the former prisoners. It will begin work with prisoners half a year prior to their release and only interested prisoners will be participating. Currently only three penitentiary institutions, all in Mahiliou oblast, are participating, with about 120 prisoners.

Turning prison from crippling into corrective institutions is a difficult but necessary task. While recidivism cannot be completely eliminated, reducing it will improve not only the lives of prisoners but also potential victims and is a less costly alternative to keeping offenders incarcerated.

The

The