A Thaw in US-Belarus Relations?

Photo: U.S. Embassy Minsk Facebook page

The Ukraine crisis has revitalised, if not improved, US-Belarus relations.

Due to his careful stance on the Ukrainian conflict as well as Vladimir Putin’s careless actions in the Crimea, Alexandr Lukashenka is no longer the main villain on the post-Communist bloc. Instead, he could become a peace broker between the warring parties.

A week ago, high-level representatives of USAID, the State Department and Department of Defence visited Minsk to discuss areas of mutual interest. This is the third visit by high-level US officials this year, and a marked change from the past.

In July, the US embassy in Minsk expanded its visa services, and the State Department reduced multiple entry visa fees for Belarusians. Economic ties could also experience a revival – the first Belarusian-American Investment Forum will be held in New York on 22 September.

Two Decades of US-Belarus Diplomacy

The US embassy in Minsk was officially opened on 31 January 1992. In 1993, Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Republic of Belarus Stanislau Shushkevich met President Bill Clinton in Washington. The following year, Clinton visited Belarus and presented a memorial bench to the people of Belarus. Installed at the site of Stalin’s mass murder at Kurapaty, the bench serves as a reminder of the only visit of a US president to Belarus, as well as a commemoration of Belarusian suffering under the Soviet regime.

Bilateral relations went steadily downhill since then, and reached a nadir under President George W. Bush. In 2004, the US Congress unanimously passed the Belarus Democracy Act, which authorises assistance for Belarusian opposition parties, NGOs, and independent media promoting democracy and civil rights in Belarus. In 2005, US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice named Cuba, Burma, Belarus, and Zimbabwe "outposts of tyranny" where the United States must promote democracy.

In 2007, the United States imposed sanctions against the Belarusian oil company Belneftekhim. Sanctions were tightened in 2008 following the imprisonment of Belarusian presidential candidate Alyaksandr Kazulin. Reacting to sanctions, Belarus demanded a reduction in US embassy staff in Minsk.

The election of Barak Obama prompted changes in the US approach to the post-Soviet space. In July 2009, less than a year after the Russia-Georgia war, Obama told the New Economic School in Moscow that the US-Russian relationship required a reset. The “reset” with Russia, however, has not alleviated US sanctions on Belarus.

On 1 December 2010, Minsk won favour with the United States by agreeing to give up its stock of highly enriched uranium. However, this important diplomatic victory was immediately overshadowed by Lukashenka’s brutal crackdown on protesters following the December 2010 presidential election. The crackdown resulted in the strengthening of US and EU sanctions on Belarus and a near complete freeze on US-Belarus relations.

The crisis in neighbouring Ukraine provided Lukashenka with a rare opportunity to mend fences with the West. Even though Washington continues to criticise the state of human rights in Belarus, bilateral dialogue and visits have gone forward nonetheless.

Friendly Autocracies Pose Dilemmas to US Diplomacy

Virtually all US official statements on Belarus reference democracy and human rights. Concluding the September visit, the Head of the US Government Interagency Delegation adhered to this longstanding US policy by reiterating US concerns over democratic standards and the state of civil society in Belarus.

On 16 September, the 15th anniversary of the disappearance of Belarusian Opposition leader Viktar Hanchar and businessman Anatol Krasouski, U.S. State Department spokeswoman Marie Harf reiterated that “[t]he families of the disappeared deserve justice.” The statement followed an appeal by Krasouski's widow, Irina Krasouskaya, who is now married to Bruce P. Jackson, an operative of the Republican Party and outspoken proponent of NATO expansion into Eastern Europe.

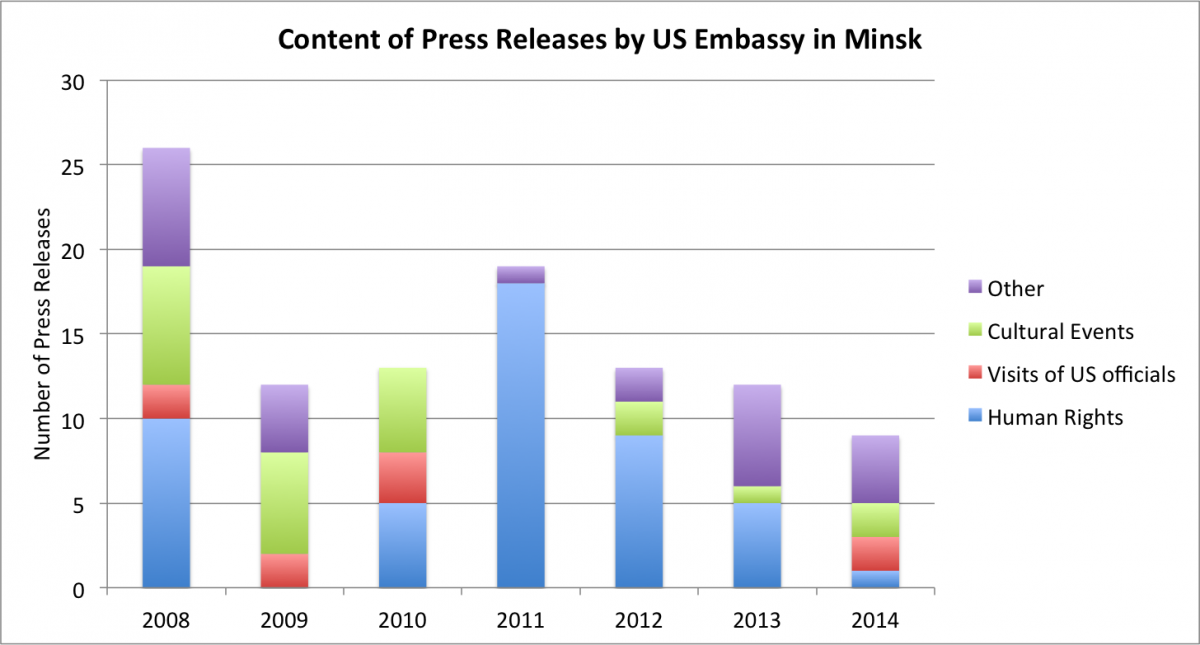

Even as the routine admonitions of the Belarusian leadership have continued throughout the years, the share of press releases by the US Embassy in Minsk devoted to human rights and democracy in Belarus has decreased over time. This year, the United States clearly has more pressing concerns in the post-Soviet region.

Indeed, the democratic deficit rarely prevents US engagement when vital security and economic interests are at stake.

In Azerbaijan, US energy companies took stakes in the oil and gas sector in spite of the regime’s authoritarian excesses. Similarly, the exigencies of the Afghan war eclipsed US criticism of the bleak democratic prospects in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan.

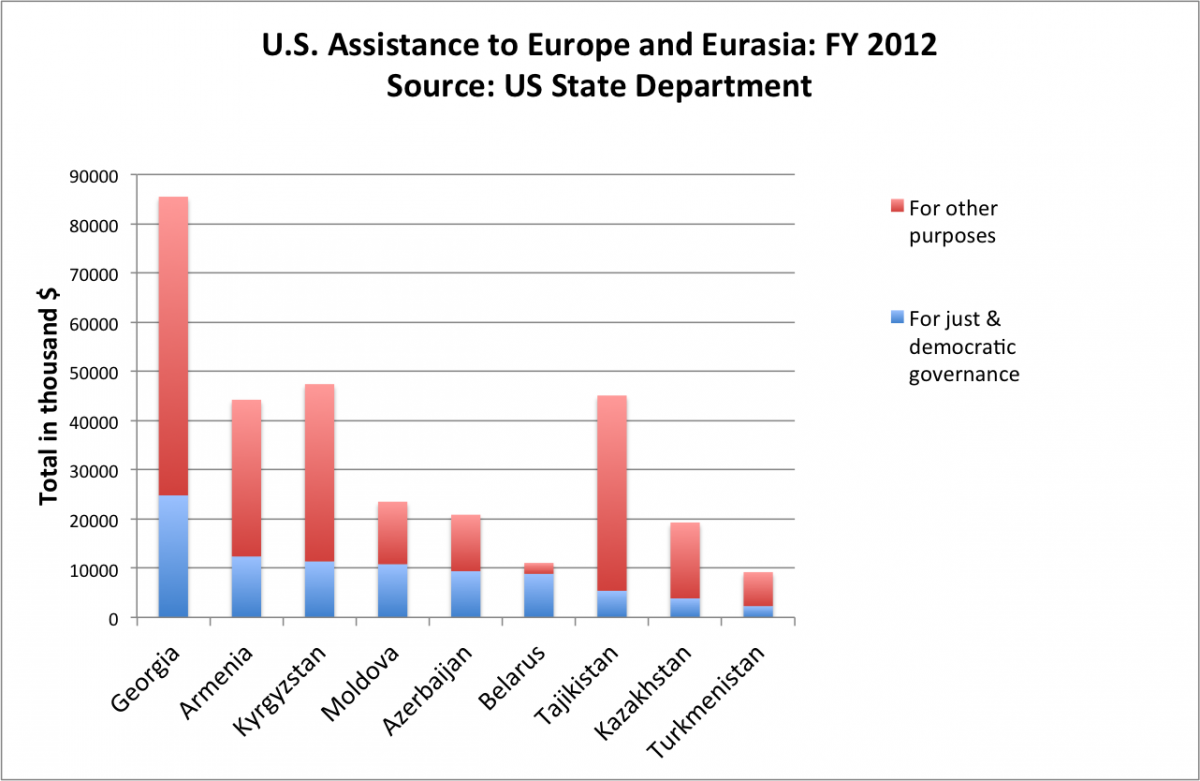

The distribution of US financial assistance in the post-Communist space demonstrates this uneasy coexistence of normative and security interests. In fiscal year 2012, Belarus received only half as much financial assistance as democratic Moldova and authoritarian Azerbaijan. What is more, although 80% of US Foreign Operations Assistance to Belarus were devoted to the promotion of just and democratic governance, only 45% of US assistance to Azerbaijan was devoted to this purpose.

What do Belarusians think?

A thaw in Belarus-US relations could become a feather in Lukashenka’s cap ahead of the 2015 presidential election. A public opinion poll conducted in 2010 by the Independent Institute of Socio-Economic and Political Studies (IISEPS) suggests that nearly half of Belarusian respondents believe it is necessary for Belarus to normalise its relationship with the United States.

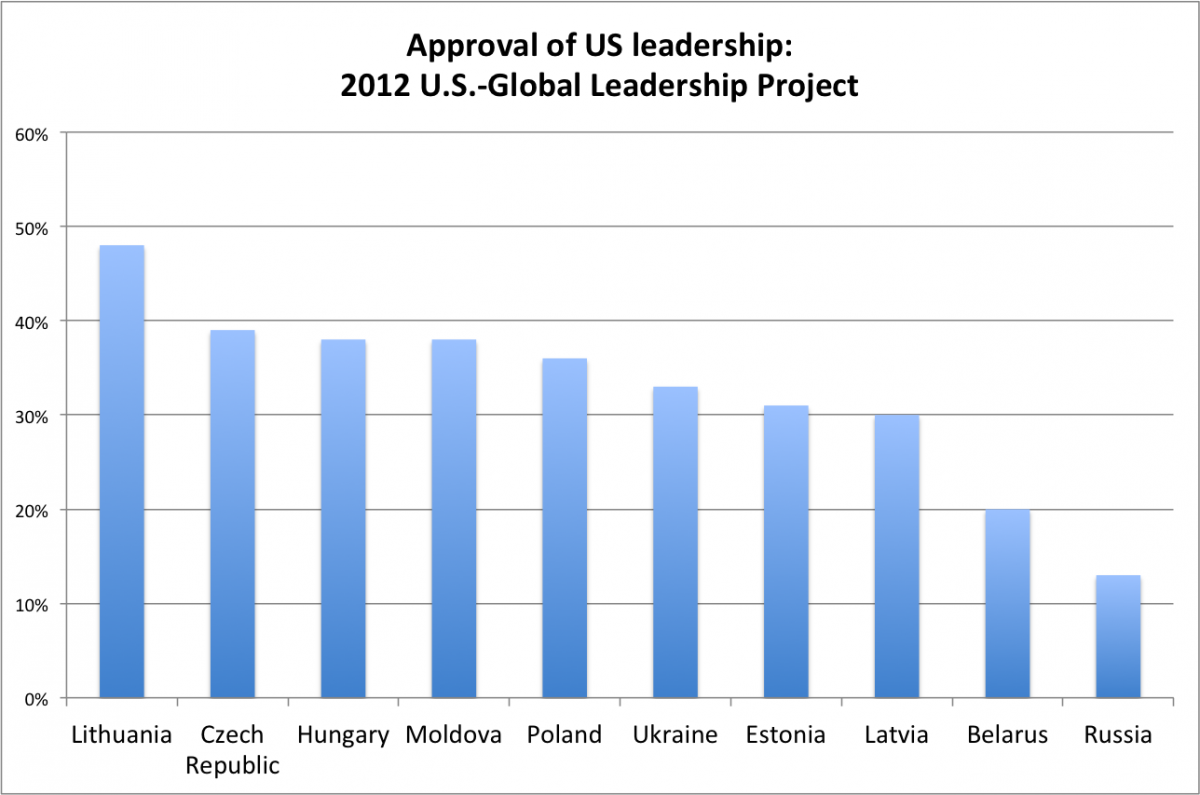

If the rapprochement fails, however, Lukashenka will not lose much. Belarusians are no more enthusiastic about the US leadership than President Lukashenka.

According to the 2012 U.S. Global Leadership Report by Gallup, only 20% of Belarusians said they approve of US leadership, with 30% disapproving and 50% uncertain. Neighbouring Russia was the European country with the lowest approval of US leadership (13%).

Putin’s son-of-a-bitch?

As US President Franklin Roosevelt once said about Nicaraguan dictator Somoza, “he is, of course, a son-of-a-bitch, but he is our son-of-a-bitch.” Throughout the last decade, Vladimir Putin may have felt the same way about Belarus’ Lukashenka, who remained an ally while at the same time initiating trade wars and arresting Putin’s oligarchs.

Lukashenka remained Putin’s “son-of-a-bitch” as the Ukrainian conflict unfolded. As far as rhetoric is concerned, Lukashenka sought favours from the West by criticising the invasion in Crimea, refusing to join Russian sanctions on Western food exports, and establishing friendly relations with the new Ukrainian leadership. At the same time, he took no meaningful actions to signal true neutrality in the conflict.

Furthermore, Lukashenka never ceased to reiterate Belarus' readiness to host Russian missiles. On 6 September, he went as far as to blame the US involvement for destabilising Ukraine and triggering escalation.

Whereas the United States has at times contradicted its human rights rhetoric with its actions, Belarus has strayed from Moscow’s line exclusively in rhetoric. The hard truth is that falling out of favour with Russia still has far more serious consequences for Lukashenka than irritating the distant United States.