Who gets official awards from Lukashenka? An analysis of the past two decades

Hero of Belarus Order. Photo: newsgomel.by

On 9 January, Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenka held his annual Presidential Prize awards ceremony. Presidential Prizes recognise achievements in spiritual revival, in sports, and in culture and art.

Over the past two decades, President Lukashenka’s personal preferences and hobbies, such as agriculture and ice hockey, have shaped who gets a prize. The highest awards still mostly go to Russian citizens, and often those from the ruling elite.

Finally, the government awards only to employees of state institutions, while Belarusian civil society’s contribution remains unrecognised.

State awards receive minimal attention in the Belarusian expert community. Belarus Digest presents a brief analysis of the main awards and their laureates over two decades and identifies the defects of awarding policies in Belarus.

Lukashenka: the primary award giver

Belarus follows Soviet tradition in having a hierarchy of awards. ‘Orders’ are the highest form of award, followed by medals, and then honorary titles. ‘State Prizes’ and ‘Presidential Prizes’ are another type of award. These are given for achievements in science, literature and arts, sports, and the spiritual sphere. Above all awards stands the title of ‘Hero of Belarus.’ The title occupies its own category and is Belarus’s single highest award.

Lukashenka presents the Award for Spiritual Revival on 9 January 2018. Photo: president.gov.by

According to the Constitution of the Republic of Belarus, the giving of state awards is one of the president’s duties. Award ceremonies occupy a separate category on the Belarusian president’s official website and are widely reported in the official media. Lukashenka gives speeches at each and every award ceremony, explaining the importance of the various laureates’ activities for the Belarusian state.

Hero of Belarus – the highest award

The title of ‘Hero of Belarus’ is the highest state award in the country. The title is given for exceptional merit related to an accomplishment in the name of freedom, independence, or prosperity for Belarus. The title was first awarded (posthumously) in 1996 to Lieutenant Colonel Uladzimir Karvat, who prevented his falling plane from crashing into a village.

At present, 11 people bear the title of Hero of Belarus. Four recipients of the title are for contributions to agriculture in Belarus. Given Lukashenka’s rural origin, agriculture has always received special attention. Three other owners of the Hero of Belarus come from industry, one in religion, sports, culture, and aviation. The most recent person made a Hero of Belarus was Darja Domračava, after she won three gold medals at the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics.

Darja Domračava receives Hero of Belarus. Photo: by24.org

The ‘Order of the Fatherland’ is the second highest award in Belarus. Belarus has three laureates of this award—two of them from sports and one in agriculture. It is worth noting that both areas relate to Lukashenka’s passions. The ‘Order of Military Glory’ is the third highest award to be bestowed in Belarus. Only one person has been awarded the Order of Military Glory—Lieanid Maĺcaŭ, who served at the highest military posts throughout most of Lukashenka’s political career.

Belarus also has a number of other orders in various spheres. They include: the Order for Labour Glory; for Service to the Motherland (military service); for Personal Courage (heroic deeds); for Friendship of Peoples (promotion of peace and cooperation between nations ); for Honour (various achievements); of Francis Skaryna (national revival, history, and culture); and of The Mother (this requires a woman to give birth to five or more children).

Friendship of Peoples Order as a foreign policy tool

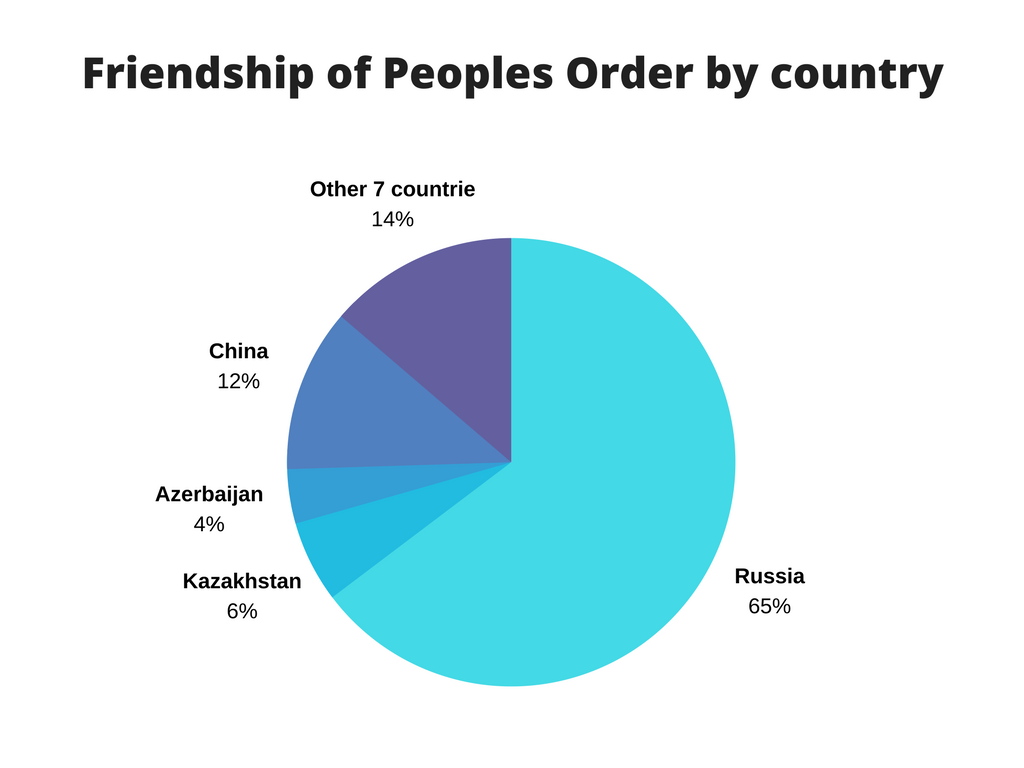

The Friendship of Peoples Order presents an interesting case for analysis, because it displays President Lukashenka’s foreign policy priorities. Out of 52 orders awarded since 2002, Russians have received more than half—29. Virtually all are high-ranking Russian officials, most of whom belong to siloviki (controllers of the security and force-wielding ministries). Putin himself has received the Friendship of the Peoples Order from Lukashenka. China, the second largest foreign policy priority of the Belarusian leadership, has the second largest number of orders—six.

Kazakhstan, which is Belarus’s partner within Eurasian Economic Union, has received three Friendship of People’s Orders. Representatives from nine other separate countries, organisations, and companies are holders of one order. Among them are Hugo Chavez, the former president of Venezuela whom Lukashenka considered a close friend, and René Fasel, president of the International Ice Hockey Federation—ice hockey being Lukashenka’s favourite sport. These cases show that the Belarusian president is decisive in choosing to whom this particular award is given. The Friendship of Peoples Order functions as Lukashenka’s personal tool of gratifying high-ranking foreign figures.

Kazakhstan, which is Belarus’s partner within Eurasian Economic Union, has received three Friendship of People’s Orders. Representatives from nine other separate countries, organisations, and companies are holders of one order. Among them are Hugo Chavez, the former president of Venezuela whom Lukashenka considered a close friend, and René Fasel, president of the International Ice Hockey Federation—ice hockey being Lukashenka’s favourite sport. These cases show that the Belarusian president is decisive in choosing to whom this particular award is given. The Friendship of Peoples Order functions as Lukashenka’s personal tool of gratifying high-ranking foreign figures.

The Order of Francis Skaryna: praising Russians, ignoring the neighbours

The Order of Francis Skaryna, which is named after Belarus’s prominent medieval book printer, is given for outstanding achievements in the field of national and state revival, achievements in the field of national language, history, literature, art, book publishing, cultural, or educational activities. More besides, it can also indicate special merits in humanitarian, charitable activities, protection of human dignity, citizens’ rights, and other noble deeds.

Since the year of its establishment in 2007, the order has been awarded to over 200 people. The overwhelming majority of them represent Belarusian official cultural institutions and other related institutions. Among the foreign holders of the Order of Francis Skaryna—much like with the Friendship of Peoples Order—Russians prevail. Aside from various cultural figures, Lukashenka gave the order to former Russian President Boris Yeltsin, Moscow Mayor Yury Luzhkov, and Duma Chairman Gennadiy Seleznyov.

Besides Russian politicians, whose cultural achievements and contribution to the national revival of Belarus seem doubtful, the Belarusian president gave the Order of Francis Skaryna to a number of Russian pop artists, including Philipp Kirkorov, Nikolay Baskov, Nadezhda Babkina and producer Viktor Drobysh. During the award ceremony featuring Drobysh in October 2015, Lukashenka also criticised author Svetlana Alexievich for her ‘anti-Belarusian rhetoric abroad.’ Alexievich, the first and single Nobel laureate from Belarus, has so far not been honoured with the Order of Francis Skaryna.

Lukashenka, his son Mikalaj and Russian pop singer Nikolay Baskov. Photo: Anton Motolko

Another important aspect of this particular order is its state-only character: all native laureates come from state institutions, while independent artists and activists remain unrecognised by the authorities.

All representatives of the ‘Western World’ on the list of Skaryna order holders have received it for charity, mostly helping children of Chernobyl. Among them is famous French fashion designer Pierre Cardin, who has contributed to various charitable activities in Belarus. Belarus’s second largest neighbour, Ukraine, has received only two orders. Representatives of Lithuania, Latvia and Poland have received none, excluding two Belarusian community activists in Poland. This fact proves the dire state of official Belarus’s cultural and humanitarian cooperation with its neighbours other than Russia.

Belarus should reform its award policy

This brief analysis of the awards exposes a number of disproportions and drawbacks in the way the Belarusian government recognises the value of certain persons for the country’s development. First, it remains heavily influenced by the personal preferences and hobbies of President Alexander Lukashenka. Thus, spheres like agriculture and sports receive an undue amount of attention in comparison to others.

Although Belarus declares its foreign policy is that of diversification, the most prestigious foreign awards overwhelmingly go to Russian citizens, and often from the ruling elite. Other neighbouring countries remain neglected, despite long historical and cultural ties with the Belarusian people.

The government dispenses awards only to representatives of state institutions. Independent creators and members of civil society remain unrecognised as contributing to Belarusian societal development. This imbalance contradicts Belarus’s new image which it has been presenting abroad over recent years.

State awards can thus be an indicator of trends in domestic and foreign policy. So far, any visible changes have not occurred despite the new cycle of warming relations with the West and independence strengthening policies of the country’s leadership.