Summary of the 6th Annual ‘Belarusian Studies in the 21st Century’ Conference

On the 18-19 February 2021 the 6th Annual ‘Belarusian Studies in the 21st Century’ conference gathered participants from various countries of Europe and North America to present and discuss academic research related to Belarus.

The University College London School of Slavonic and East European Studies (SSEES), the Ostrogorski Centre and the Francis Skaryna Belarusian Library and Museum co-organised this year’s conference.

It welcomed 25 scholars who presented their research on Belarus with particular focus on the 2020-21 protests.

Opening Remarks

Professor Yarik Kryvoi, the Ostrogorski Centre, thanked the speakers for their contribution towards the demystification of Belarusian politics. Uprisings have never resulted in regime change in the history of Belarus. The unprecedented Belarusian protests of 2020-21 show that the potential for political change is unlikely to be lost.

Dr Andrew Wilson, the University College London SSEES, equally recognized the importance of research on the political history of Belarus. Dr Wilson announced the possible addition of an individual course on Belarusian history at the SSEES.

The Origins of the 2020 Uprising in Belarus

In his keynote speech Professor David Marples, University of Alberta, addressed the “question of when”. His view is that political change will occur when Alexander Lukashenka leaves office.

Both the myth of the Great Patriotic War and the appropriation of the Stalinist legacy serve to solidify the foundation of the authoritarian regime in Belarus. The lack of efficient response to the Covid-19 epidemic shows how a mantra of ignorance is strength also pervades the present.

The unprecedented size of protests in Minsk on the 23 August 2020 marked a turning point. Professor David Marples disagrees with Belarusian sociologist Oleg Manaev’s opinion that little has changed. The Belarus of Lukashenka is not there to stay for too long. Rural support has corroded, the Parasite Law has broken the state-worker social contract and Lukashenka has failed to offer economic change. Most importantly, an unprecedentedly large, dissatisfied population continue to protest in the cities of Belarus. It is demographically diverse and continually growing.

Political change will occur, but can only occur without Lukashenka. Ultimately, the economic situation will decide whether this will happen by decision or by force. For the dissidents it is a question of time, for the regime a question of fear and survival.

Lukashenka’s Ivory Tower at Home

The first panel of the day chaired by Prof Andrew Wilson from UCL focused on state media use. Dr Stephen Hall, University of Cambridge, used a collection of interviews to explain why Lukashenka has failed to understand his people. Policy briefs by the State Security Committee effectively cater to his own narrative. Lukashenka has built himself an ivory tower.

Andrei Kalavur, Masaryk University, presented on the state media campaign during the elections. Lukashenka’s lack of understanding of the power of non-state digital media meant that he never changed his campaign. In the lead-up to the 2020 elections Natallia Eismant, his press secretary, repeated the same “information dramaturgy”. The aim was the manufacture of crisis to promote the need for a strongman. Once more state press demonised the opposition, once more it warned of impeding external threats. It nothing but fatigued the Belarusian people.

Dr Nataliia Steblyna, Vasyl Stus Donetsk National University, analysed state media discourse. She compiled state media sources from 2005-2019 to create indices. These showed a significant increase in the representation of political actors and in political emotions. She also spotted a gap in digital coverage from 2005-2008. Only after 2008 did the state begin to disseminate its discourse digitally. The delayed response made possible the spread of network communities with alternative agendas. The internet became the adversary of the state.

Potemkin Village Abroad

A focus on foreign relations matched the domestic focus. Yahor Azarkevich, University of Glasgow, compared the foreign policy operational codes of Alexander Lukashenka and Donald Trump.

A focus on foreign relations matched the domestic focus. Yahor Azarkevich, University of Glasgow, compared the foreign policy operational codes of Alexander Lukashenka and Donald Trump.

He compiled sources from 2010-2020 through the Verbs in Context System. Similar to Dr Steblyna’s research, he concluded that Lukashenka’s foreign policy discourse remains relatively stable.

Dr Sándor Földvári, Debrecen University, addressed the recurrent topic of Belarus’ foreign policy of drift. Although economically dependent on Russia, if Orban’s Hungary can exist in the EU then so could Belarus. The panel discussion spotted a lack of literature on the question of EU investment in Belarus. Dr Földvari encourages further research on this topic.

The presentation of Ekaterina Pierson-Lyzhina, Université libre de Bruxelles, discussed the multi-vector foreign policy of Belarus. This policy consists of a strategy of economic dependence on Russia and soft power rhetoric with the EU. The doors of the EU are now closing, however. Opportunism can only work for so long.

The Opposition

Dr Volha Charnysh from Massachusetts Institute of Technology chaired the final panel focused on the identity of resistance.

Dr Volha Charnysh from Massachusetts Institute of Technology chaired the final panel focused on the identity of resistance.

Dr Sasha Razor presented an incredibly engaging visual presentation on articulations of national identity through protest art. The medium of embroidery, by artists like Rufina Bazlova, shows that protesters have chosen white-red-white as their symbol. The red thread which weaves through all protest art is the binding call for a democratic end to violence.

Aliaksandr Kazakou, an independent researcher from Belarus, reengaged Professor Marples’ point on state appropriation of the Soviet period. Protesters carefully dodge everything which makes up the inherently repressive state discourse. Their national identity formation stands in antithesis to state discourse.

Lastly, Dr Joanna Getka presented on the visual contra-propaganda of the protest. Behind its playful and mocking nature lies rapid self-organisation and civil solidarity.

The first day closed with a vibrant discussion between panellists and attendees as to what, if not solely the slightly restrictive passport, constitutes Belarusian identity. The second day shifted the focus from contemporary political developments to the history, society and culture of Belarus.

Belarusian Historical Memory

The next chapter focused on Belarusian historical memory and was chaired by Dr Alena Marková from Charles University.

The next chapter focused on Belarusian historical memory and was chaired by Dr Alena Marková from Charles University.

Dr Aleksandra Pomiecko, University of Manitoba, opened with a study of the Sluck insurrection of 1920, the first national uprising. Soviet historiography had wrongly discarded the insurrectionists as solely counter-revolutionary in aspiration.

The Belarusian state neither approved nor disapproved the Soviet narrative. Today, protesters view Sluck as an example of individuals fighting for their national belief.

But national identity is not majoritarian. Professor Boris Czerny, the University of Caen, has studied the Jewish population of Brest-Litovsk in 1915-18. An investigation rich in primary sources recounted the identity struggle of a population trapped between two occupying forces and a diktat treaty. Professor Czerny emphasised that 1916, the Jewish population trapped in war, necessitates a connection to 1942, its genocide.

Maryna Laurynovich, Charles University, concluded with a chronological study of Piotr Masherau, the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Byelorussia. Previously, the figure of Masherau had personified the state’s founding myth. Then it steadily fell into the ash heap of history.

The Formation of a National Identity?

The second panel of the day focused on social history and chaired by Dr Peter Braga from UCL.

The second panel of the day focused on social history and chaired by Dr Peter Braga from UCL.

Dr Alena Marková, Charles University, agreed that Belarusian national identity has always formed under the auspices of the Soviet past. Identity formed after the state. The 1990 Law on Language saw letters of support in Belarusian, but also in Russian.

Mark Cinkevich, an independent researcher from Belarus, presented on the formation of state identity. To Miss Woolley’s question of whether Soviet history has swallowed up Belarusian history this presentation too answered with a resounding yes. Belarusian society never came to terms with its Soviet past because instead of de-Stalinization the state reappropriated the Soviet legacy.

Lizaveta Dubinka-Hushcha’s research at the Copenhagen Business School usually involves the international relations of Denmark. It was the intriguing story of the Cross of Dagmar which inspired a research detour on St Sophia of Polotsk. Based on consultations with Belarusian goldsmiths and her academic research she confirmed the high probability that the cross of Dagamar originated from Belarus.

Symbols of Belarusian Culture

Dr Karalina Matskievich from the Francis Skaryna Belarusian Library and Museum chaired the final panel. It focused on cultural history.

Dr Karalina Matskievich from the Francis Skaryna Belarusian Library and Museum chaired the final panel. It focused on cultural history.

Vitali Byl, University of Greifswald, presented on Ruthenian witchdoctors in the Lithuanian witch-hunt. Until the Catholic Church started to persecute witchdoctors their healing practices had symbolised folk culture.

Dr Simon Lewis, University of Bremen, spoke about poetry and music in the contemporary culture of the protests. In an expression of national solidarity poets have become leaders. At the end of the presentation, he recited The Stone of Fear, a poem by Julia Cimafiejeva on the suffocating fear of repression passed down from generation to generation.

A.M. LaVey, University of Rhode Island, showed how Belarusian textiles constitute national identity. Mr LaVey emphasised Dr Razor’s argument that embroidery and protest dovetail. Belarusian textiles developed from a utilitarian object into a political symbol. Meanwhile, national costume transformed into a state symbol. It is state resentment which gives potential to symbols of protest.

Concluding Remarks

The University College London School of Slavonic and East European Studies, the Ostrogorski Centre and the Francis Skaryna Belarusian Library and Museum kindly thank the speakers. Many presenters will have the opportunity to turn their research into a journal article published in The Journal of Belarusian Studies.

Daniel Szöke

Videos of each conference panel are available here.

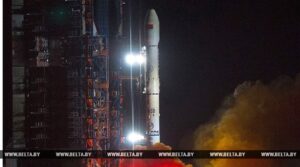

Later, in October 2018, the second satellite, constructed by Belarus State University for research purposes, was also launched into space with Chinese help. On 31 August 2020, Lukashenka signed an executive order concerning the launch of the second satellite, to be constructed by Belarus State University in 2021. Although no details concerning the launch have been published, most probably it will be done with Chinese help too.

Later, in October 2018, the second satellite, constructed by Belarus State University for research purposes, was also launched into space with Chinese help. On 31 August 2020, Lukashenka signed an executive order concerning the launch of the second satellite, to be constructed by Belarus State University in 2021. Although no details concerning the launch have been published, most probably it will be done with Chinese help too.