Analytical Paper: Belarusian Identity – The Impact of Lukashenka’s Rule

The regime of Aliaksandr Lukashenka rejected the ethno-national model of state suggested by his predecessors in the early 1990s.Instead, he restored a soviet style “statist nation” with a centralised bureaucratic machine at its core.

These are the conclusions reached in a new analytical paper "Belarusian Identity: The Impact of Lukashenka's Rule" released by the Centre for Transition Studies today.

Identity issues, particularly those surrounding language and historical narrative, formed the foundation of the persisting cleavage between the authoritarian regime and the democratic opposition in Belarus since 1994. The population of the country, although not nearly as divided with regard to its identity as Ukraine, also has not produced a consensual version of self-determination.

The paper presents an analysis of the processes in Belarusian national identity, particularly with regards to its language, historical narratives and self-contextualisation in an international setting since its independence, especially under the rule of Aliaksandr Lukashenka.

Based on a number of empirical studies, it attempts to trace a detailed picture of the impact of the political regime and its major political and economic interests in the formulation of Belarus’ national identity.

Lukashenka’s Identity Policy

Shortly after his election in 1994, Aliaksandr Lukashenka launched a policy of russification. The rationale behind it seemed clear – Lukashenka chose Russia as a strategic priority for Belarus’ foreign relations, hoping to quickly recover from the economic crisis through re-establishing Soviet economic ties. The other reason for the pro-Russian politics of the regime stemmed from the anti-Russian discourse of opposition. Although ideologically diverse, it was associated with the right wing Belarusian People’s Front and state propaganda labelled it with radical nationalist ideas.

In 1995, Lukashenka initiated a referendum to introduce Russian as a second official language in Belarus. 83.3% of voters supported the initiative. From this point on the Belarusian language has suffered a major decline. Although the Constitution of Belarus declares the equal status of both languages, Russian de facto dominates all spheres of life. The Law on Languages of 1990 does not set strict rules on the use of both languages in the day-to-day operations of the state, and public organisations and officials usually use Russian.

Since the early 2000s all major Belarus-based media broadcasts in Russian, leaving Belarusian only a small quota in cultural sphere. Apart from Minsk, not a single fully Belarusian school currently functions in any other major cities in Belarus. In higher education, the picture is rather similar – an all-Belarusian language university does not exist in Belarus.

The paper notes that most of the population take a more pragmatic stance towards the language issue and follow the example established by the ruling elite. The only actor that has made any serious attempts to revive the Belarusian language and introduce it into public life is civil society.

Trends in Language Use: a Russian-speaking Belarusian Nation

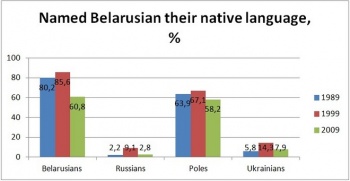

As the data on identity and language use from recent decades show, the proportion of those who identify themselves as Belarusians is increasing, but the use of Belarusian has dramatically declined, leading to the formation of a Russian-speaking Belarusian nation.

Only a quarter of Belarusians speak Belarusian at home, which roughly equals the number of the total rural population. In Minsk, the number of people who indicated Belarusian as their native language has decreased almost two-fold over 1999-2009. In general, only a little more than 10 per cent of the urban population of Belarus speaks Belarusian at home, and in its largest cities this number is much smaller.

The region with the highest percentage of Belarusian-speakers is the one to the northwest of Minsk on the Lithuanian border. Interestingly, this particular region historically correlates with the most the pro-democratic and anti-Lukashenka voting area.

Politics of History and Self-Awarenes: Soviet Glory with a Mediaeval Flavour

Lukashenka’s narrative of history, however, managed to reconcile the nationalist version of history of the pre-Soviet period with its own modern conception of Belarusian history. They both agree that Belarusian statehood has a long tradition of independent existence and is valued by all Belarusians.

Also, unlike the Soviet version of Belarusian history, which involved class struggle and Russia-centrism in every period of Belarusian history, the official narrative does not pay much attention to the class-based approach nor does it seek to prove the ancient roots of Belarus' friendship with Russia. Still, the period of independence (since the early 1990s) remains the most ideologically charged and distorted issue, as it involves the rule of Lukashenka himself.

The self-awareness of Belarusians experienced massive influence from the Lukashenka regime's ideological discourse. It presents a mix of both nationalist and Soviet concepts and therefore creates the same mixed view in the minds of people, who know their roots are to be found somewhere in a mediaeval European context, but at the same time respect Soviet symbols.

When asked “What unites you with other people of your nationality?”, Belarusians most often refer to territory and state, rather than culture and language. Political unity based on the state serves the core idea of the official ideology of the Lukashenka regime.

Belarusians see the origin of Belarusian statehood in mediaeval Polack and Turaŭ princedoms and the Great Duchy of Lithuania, not in the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic. Yet at the same time they have already accepted the symbols that the Lukashenka regime introduced in the 1990s, such as national holidays and the red-green flag.

Geopolitical Choice of Belarusians: Pragmatism without Soviet Sentimentalism

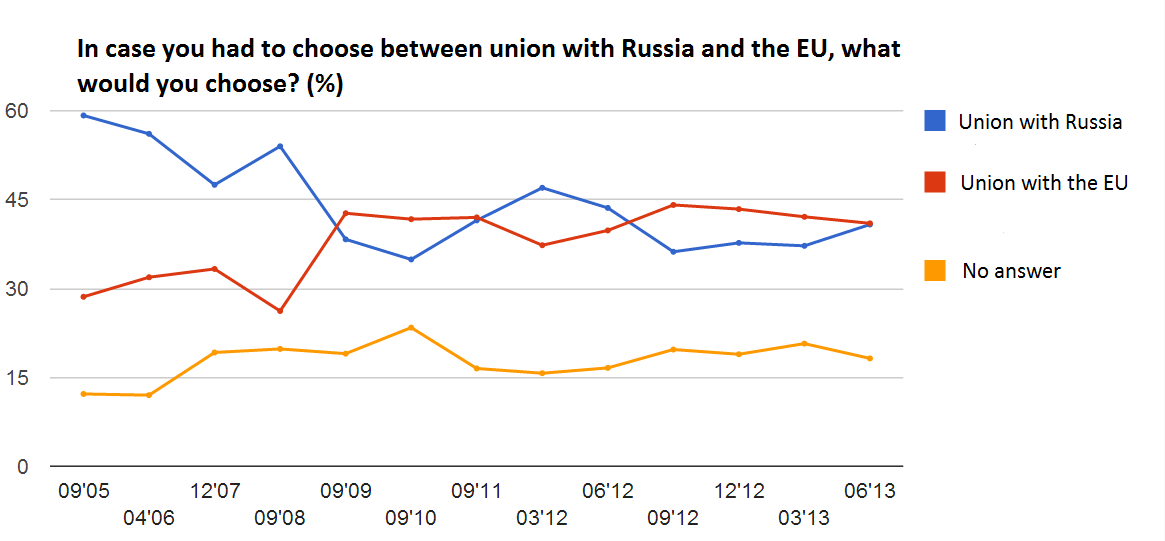

The studies reviewed in preparing the analytical paper showed that the geopolitical views of Belarusians express a purely utilitarian understanding of foreign relations and are ready to join that integration project which will offer them the most economic benefits.

These views, in many ways, resemble the opportunistic foreign policy of Lukashenka’s regime, which seeks momentary benefits without any concrete strategic approach.

A large number of Belarusians express isolationist views, while others are divided in deciding between the east and the west. No consensus on this matter exists in Belarusian society and Belarus truly remains a place where civilisations clash.

Although Belarusians are often considered a Soviet-style nation that persists in holding onto the USSR’s legacy, and contrary to popular thought, the people actually do not want to witness the restoration of Soviet power.

- Download the full text of Belarusian Identity: The Impact of Lukashenka's Rule.